Last week, I discussed the pros and cons of regulation in the context of regulatory reform. This week, I dived into the literature/writing surrounding regulation to see what ideas were out there for regulating more wisely. Here’s a few of the many good ideas I came across.

Flipping the Script on Regulatory Review

Mansur Olson, a giant of the public choice tradition, did a phenomenal job of calling attention to the role that concentrated benefits and dispersed costs play in creating and maintaining special interest groups. These groups have a vested interest in preserving the status quo while their opponents struggle to organize, making it hard to organize around the repeal of certain regulations.

But by always framing regulatory reviews (and any consideration of a regulation) in terms of why it should be kept, not why it should be cut, we can mitigate this. It becomes a matter of forcing special interest groups to defend themselves rather than making the public organize against them (reducing their leg-up.) We could even take inspiration from the highly successful military base review process, which was able to confront and overcome large-scale opposition to the shuttering of military bases across the country.

Focusing on Issues with Bipartisan Appeal

At the moment, regulatory reform is a bit controversial. On the left, it is often framed as a handout to the rich and powerful that harms everyday Americans. On the increasingly ascendant populist right, it is less disliked but still controversial. By focusing on issues with bipartisan appeal, Congress and other government actors will be able to improve the regulatory environment in multiple sectors without squandering valuable political capital.

Creating (or strengthening) Regulatory Review Subgroups or Agencies:

At the moment, much less attention is paid to the general regulatory stock than new regulations and proposals. By forming a new agency or commission — or even just strengthening or adding groups within existing organizations — whose task is solely to find and either repeal or improve bad regulations, we could improve how we regulate without relying solely on concerned citizens and groups (who will likely only target specific regulations) to do the work. These groups could be incentivized to do their work by providing financial incentives tied to their work (though care would need to be taken to ensure they don’t provide a perverse incentive for excessive deregulation.)

This group doesn’t necessarily need to focus on deregulation either. Instead, they could take the place of the groups who currently review regulations and work to improve the regulatory review process, seeking to remove only the things that aren’t absolute necessary.

Adding More Regulatory Sunsets

There are regulations on the book that are largely irrelevant today, and regulations which are poorly designed yet have not been overturned/opposed for various reasons. By establishing that all regulations will be retired unless actively renewed, regulatory sunsetting flips the script. Unnecessary regulations will disappear once they hit their expiration date (reducing regulatory compliance costs and shrinking the burden on regulators) and more attention will be drawn to regulation, making regulators more accountable. It can also help the legislature improve the balance of powers by providing extra checks on federal authority.

Expanding Regulatory Sandboxes

This idea has already been tried on the state level and internationally with notable success. In fact, I first learned about the idea from James Cziernawski, who played a critical rule in advocating for them in Utah, who I had the pleasure of chatting with last summer. Regulatory sandboxes let certain businesses operate under a greatly reduced regulatory burden — albeit with supervision to ensure they don’t do anything bad — for a year or two. By seeing how they perform, what went right, and what went wrong (if anything went wrong), regulators can get real insights into what is and isn’t necessary.

More Regulatory Budgets

A regulatory budget establishes a strict cap on the maximum number of regulations, and often goes as far as saying that for every new regulation or order issued, some amount (usually more than one) must be repealed. This provides a strong ceiling on the total numbers of regulations in circulation and generally leads to wiser regulatory choices. It also can be a powerful way to reduce the total regulatory stock.

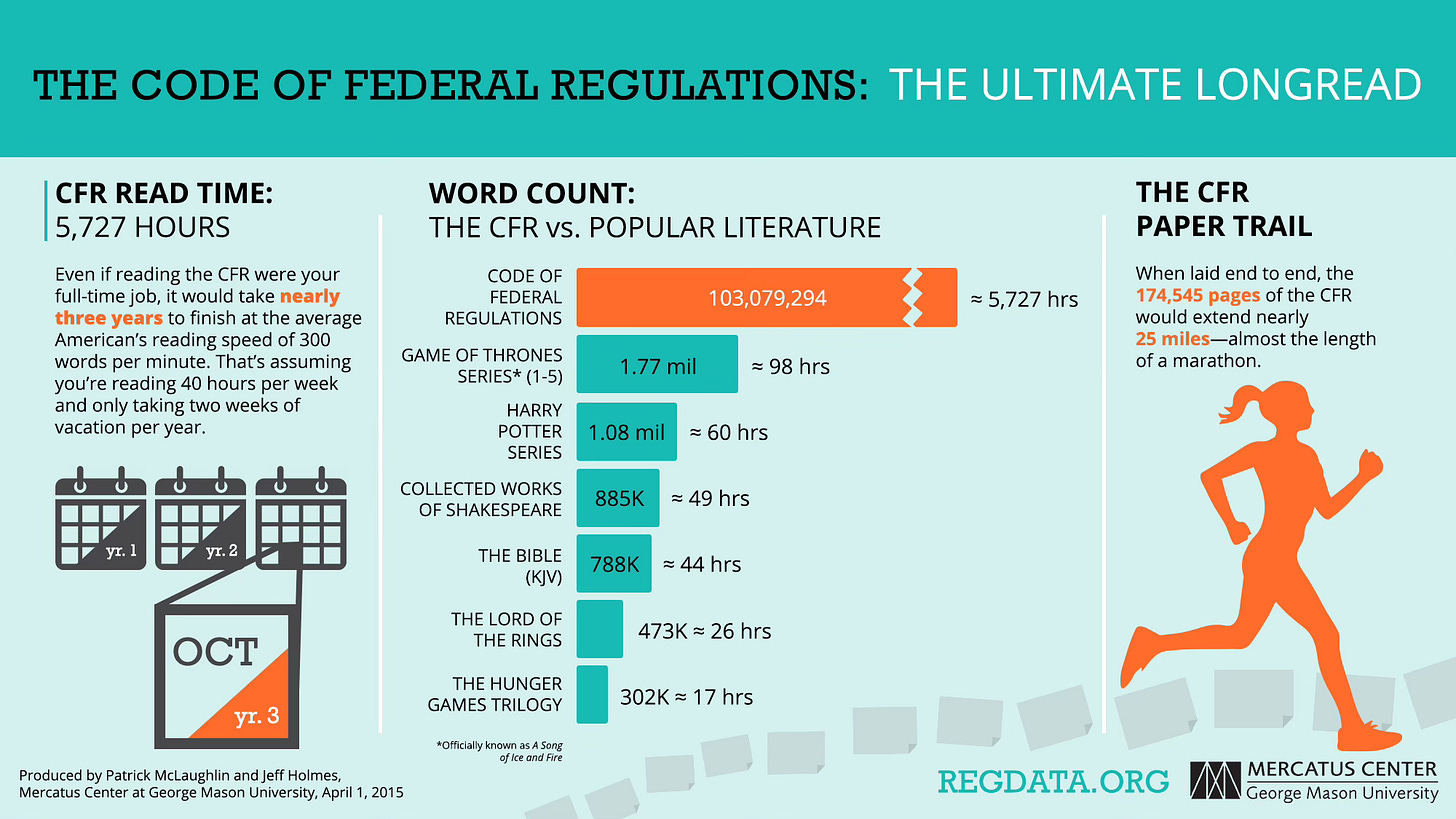

Leveraging More Technology

It can be quite difficult to understand the scope of current regulations and identify inefficiencies, redundancies, and other problems that need to be correct. After all, the number of rules and regulations is in the hundreds of thousands. Thankfully, developments in machine learning and natural learning provide new ways to understand and explore federal regulation. The Mercatus Center’s QuantGov Project has already done phenomenal work in this area, though more remains to be done.

By investing more in technologies, government agencies (including existing and potential ones) can reduce the amount of unnecessary regulations they issue, better understand the existing regulatory space, and even identify old regulations for repeal and/or alterations. The result would be a much better regulatory system.

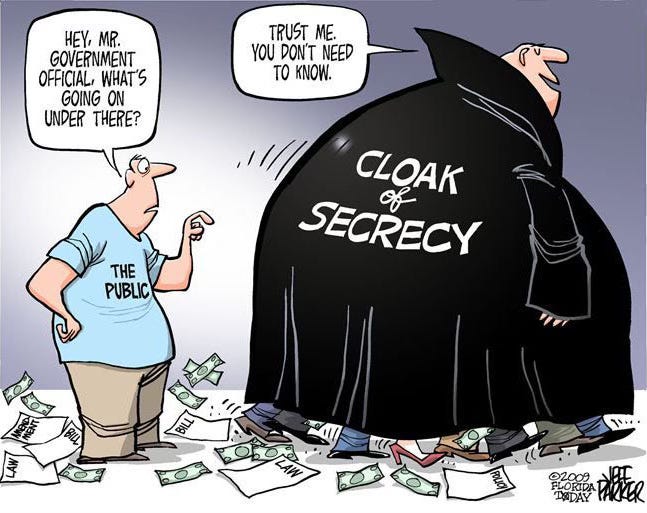

Improving Transparency and Increasing Business-Regulator Interaction

Two of the biggest critiques of regulators and bureaucrats are their general lack of accountability to the public and the opaqueness of their operations. By expanding the extent to which their work is transparent (for example, by allowing citizens to track the status of an application for something required by a regulation) regulators will be incentivized to work faster and more effectively. After all, if the public can now tell just how long a regulator is taking to do something — or the impact of a specific regulation — they are more likely to call on their representatives for assistance. At the same time, regulators who are doing a good job can be recognized and will hopefully be criticized less. This would present a carrot and stick system of incentives for regulators to be more efficient and effective.

Additionally, by increasing the amount of interaction between regulators and businessmen — such as by mandating monthly conversations, regularly embedding bureaucrats into businesses, or encouraging businessmen to spend time working for regulators — the government can reframe the relationship between the regulators and regulatees. Regulation can become a source of and venue for cooperation between regulators and businesses — who now better understand each other's perspectives — rather than a place for competition.

Outcomes Over Process:

One of the most effective ways to regulate is to emphasize what matters: outcomes. After all, there are often many paths to the same goal, and there may either be no one best path or potential paths that only one person is thinking of. By focusing more regulations on set goals and thresholds and allowing businesses to choose how they meet them, regulations can largely achieve the same thing while causing less problems.

However, outcomes will not always beat out processes. There will undoubtedly be some areas where processes stays king, and the existence of Goodhart’s law means that choosing a specific outcome or set of outcomes may not be wise.

Conclusion

Regulations are not necessarily good nor bad. They have a place and purpose, but can be easily done both poorly and well. The strategies I’ve discussed this week provide promising ways to make sure we do regulation at least a bit better.